Abner Sundell was a writer of pulps & comics; he's not exactly famous like a Kane or a Morrison, but he made a living. More Salieri than Mozart, he made not have created any JLA characters, but he laid down the law over 50 years ago on How To Write SuperHero Comics.

Let's take a look at some excerpts from his treatise and see how they reflect on the comics of today, shall we?

Sundellian Axiom 1.

All comic characters live in their own world to the complete exclusion of all other comic characters. Consequently, Batman, in his strips, is the total of heroic qualities; however, if Batman were to be compared with Superman, in the same story, Batman would immediately become a subservient character. Therefore the writer must create his own world for his heroes, a world in which the hero is the only hero.

Thank goodness poor Abner never had to write World's Finest or Brave & the Bold! This particular piece of advice is dated, a relic from a pre-"universal" approach to comic book characters ... but that doesn't mean it's entirely wrong!

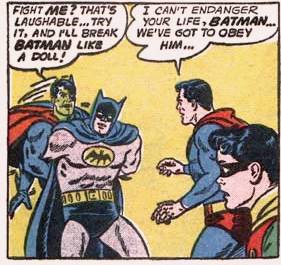

In the heyday of World's Finest, for example, Batman was clearly outclassed by Superman. My favorite such moment is in the famous Composite Superman story, where the villain says to Superman: "Fight me? That's laughable. Try it and I'll break Batman like a doll!" Gotta give C-S props for telling it like it is.

In the heyday of World's Finest, for example, Batman was clearly outclassed by Superman. My favorite such moment is in the famous Composite Superman story, where the villain says to Superman: "Fight me? That's laughable. Try it and I'll break Batman like a doll!" Gotta give C-S props for telling it like it is.Aquaman is a particular victim of Pale Comparison. Many people's exposure to Aquaman is confined to his stints with the Justice League/Superfriends, where he doesn't necessarily shine. It ain't easy to look impressive when the only people you're ever seen with are Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman, and you're hanging out on their turf, not yours.

A favorite editorial trick to jumpstart a new character in a new title is to have an important hero guest-star about three of four issues in (usually Batman, Superman, or Wonder Woman; never Aquaman *sigh*). It's designed to get general readers to pick up the book and develop interest in the new character. I wonder, however, whether the strategy doesn't backfire, hurting more than it helps. The reader picks up the book for the guest-star and notices that, in fact, the new character pales by comparison, permanently denting the reader's opinion of him or her.

Axiom 1 is also the crux of the need for every hero to have his or her own Fictionopolis.

Sundellian Axiom 2Hm. Let's just put this one write in the enevelope marked, "Special Delivery: Joe Quesada" and move on, okay? Actually, before we do, I'll note that many of my favorite characters fall into the Victims of Axiom 2 Category, such as Vibe, Aquaman, the Riddler, and Killer Moth. There's nothing intrinsically wrong with any of those characters; their principal problem is the lack of respect their writers have had for them.

Comic heroes must be treated by their writers with respect. Too often a writer thinks, "Well, he's just another comic-mag hero, the kids have seen hundreds of them."

Sundellian Axiom 3.It kind of amazes me how out of pride writers will flout conventions of the genre like this one: "That may be true for lesser writers and lesser characters, but my writing and character are different and therefore more interesting." Uh-huh. Well, short basketball players are different and interesting, too.

A hero must represent to the reader an image with which he can associate himself. Therefore he should be constructed as to be recognizable as a human being. He should have a home, or at least a setting. He should have characters to which to tie himself, friends, a father influence that makes him more understandable and sympathetic to readers. This explains the double identity formula adopted by most superheroes. Because once in uniform the hero becomes too perfect to have any human frailties, he adopts another character, much more human and understandable, so that the readers can know him better. In uniform Superman is far too perfect for one to associate himself directly with him. But as Clark Kent, a nearsighted guy who can't get to first base with Lois Lane, the readers can see themselves, and gloat in the secret that they, too, are really Superman.

Flouting Axiom 3 has harmed several characters I like, such as the Martian Manhunter, Aquaman, Wonder Woman, and the Flash (and many more characters I don't like, such as most of Marvel's line; probably part of the reason I don't like them).

And by "flouting" I don't just mean "not having a private identity". One of the things that has helped Superman and Batman's popularity over the decades is the steadiness of their supporting cast, a virtue they enjoy as a result of being created in the days before every new writer felt it was his right, nay, obligation to complete change a character's context and supporting cast. If DC's editors had the cajones to say, "See these? These are the supporting cast for all our principal heroes and they will remain so for the next fifteen years," you'd be surprised how much that would allow those characters, and the heroes they support, to grow in popularity. "Creator freedom" is overrated; I think writers become more creative when the editors give them clearer lines within which they may color (and I think the last several years at DC are evidence of this).

Sundellian Axiom 4

This is the most neglected principle of story in the comic magazine business: too often a story ends "smack" with the climax action. The reader turns the page, anxious to taper off his story, and discovers himself on page one of the next story. The denouement is the breathing spell, the return to normalcy, the tying up of loose ends, explanations, coming together of the characters at the end of the story. It should not be neglected. It does not need to be more than three or four panels, a page at most. In the denouement the opening suggestions of the next story can be planted, so that the reader is instilled with a desire to purchase that next issue. This means more than just a final caption, it means that somewhere in the story we allowed one thread to run loose. In tracing down this thread we find that it is the forerunner of an entirely new story. Thus we have created a reason for sales of the next issue.

On the whole, most writers get this and do this, I think; am I mistaken?

Sundellian Axiom 5

A successful comic character needs more than just good action plotting. He needs constant character development that will keep him as interesting to the readers two years hence as he was in his first issue.

A good method of obtaining constant characterization is through the Dick Tracy, Terry and the Pirates formula of creation of sympathetic characters, from story to story, dropping these characters for three or four months, and then at a later date involving them in another story. In this way the constant reader feels that he has been rewarded for his faith in the magazine, and the transient reader feels that he has missed something, and perhaps this would be a good magazine to read steadily.

Golden Age writers weren't stupid. Neither were they fanboys of their characters, taking their long-term appeal for granted. They understood that (1) there had to be character development and (2) it was best done with ancillary characters so that the principal and supporting characters could remain recognizable.

Sundell Axiom 6

Villains must think and act in a spectacular manner, since if they are ordinary, all actions stemming from them are ordinary, and consequently the more cunning and clever they are, so the action of the story becomes more clever and cunning. As in all good writing, action stems from response of character to situation - so it must in comics.Conceive a good villain and drop him into a mediocre situation, and if the writer is sincere, this well-conceived villain will develop a well-rounded story from his reactions to the mediocre situation. A comic lead story which depends on melodrama can be no stronger than its most melodramatic figure - therefore the importance of strong super-villains.

Axiom 6 is why I suspect that Gail Simone, who understands it, is secretly the illegitimate child of Mr. Sundell. It's also the basis for a story I desperately want to read: "Killer Moth and Cavalier Go Shopping At Wal-Mart".

Sundellian Axiom 7Or the non-rescuing. Poor Gwen Stacy, Aquababy, & Spoiler.These are characters who are vulnerable. These are the friends, and consequently the weak points, of the hero. While a hero himself cannot be hurt by bullets, these same bullets can kill his sweetheart. Thus suspense grows from danger in which important sub-characters are placed, not upon the dangers which threaten the hero himself - except how these dangers threaten him in relation to the accomplishment of his task, which very often is the rescuing of the sub-character.

Sundell Axiom 8

Boy and Girl Assistants, and generally uniformed super-assistants to lead characters, should be treated in the same manner as heroes. These characters must be written into the plot. It is insufficient to have Davey tail along with Magno and merely swing in on the action as just another fist. The story must be written that Davey serves a definite purpose. Each character must serve in some way to further the story. A character who is merely an appendage is useless, and while they may not be detrimental to the story, they certainly do not help it. Very often, while the hero is invulnerable, the boy or girl assistant is otherwise. Consequently, if properly used, the assistant can serve as an Achilles heel. Too much stress on this point only succeeds in making the boy assistant a millstone around the neck of the hero, and instead of being an heroic figure in the eyes of the reader, he becomes a bothersome one.

This is a real test of a superhero writer: how well they can walk this difficult tightrope in the use of sidekicks. Nowadays, the easy way out is taken and "sidekicks" almost never appear with the heroes they are theoretically attached to.

Except Robin. That's part of the reason Robin is so much cooler than other sidekicks; he can appear solo or with his principal without looking either too good or too bad. Oh, and Davey,too; we all know how exciting it is when Davey ably assists Magno.

Is it true that Brian Michael Bendis is working on a Magno & Davey revival?

Is it true that Brian Michael Bendis is working on a Magno & Davey revival?Sundellian Axiom 9

Too often characters are introduced into a story by an incident and then allowed to drop out entirely. This is wasteful writing. In the April issue of Lightning Comics, the Eel destroys a ferryboat. For a panel or two we see a mother who has lost three sons in the action. She speaks a piece and a character is born with a strong motivation for disliking the villain, in fact a far stronger motivation than the hero has. But she is not utilized from that point on. This is a perfect example of bad writing. Due to this characterization of the woman, we create human interest. The readers waits expectantly through the entire story for the woman to reappear, and when she does not, he is disappointed.

Calling Esther Maris...!

Sundellian Axiom 10

Suspense in comics is not attained by placing the hero in mortal danger. The reader realizes that the hero will not be injured. Suspense is attained by creating a situation in which the problem is, not whether the hero will be killed, but how he will escape in jeopardy. Or how he can escape in sufficient time, to save those vulnerable beings who are also placed in jeopardy. Or how he can escape in sufficient time to frustrate the villain's plan, which is drawing to its culmination.

Do what I do. Carry this axiom printed out on 3x5 cards, and hand them out every time a skeptic scoffs at a comic book cliffhanger. It will save you SO much time in your day...!

Sundell Axiom 11

A writer of action should also consider that good writing style can often make a chase and a fight interesting in the written story. However, when translated to pictures, the same chase and fight become unimportant when buried an a magazine full of chase and fight. In writing comic action, the writer makes his setting of primary importance. All action taking place within this setting will be indigenous to it and consequently different pictorially from action that takes place elsewhere. In a steel mill, action will be conveyed through molten metal, swinging cranes, giant machines, etc. Aboard ship, action all take place in staterooms, engine rooms, around the rigging of the ship. Too much action loses its importance. In a room full of shouting men, no one is heard; in a room full of whispering men, the shouter immediately gets attention. Action therefore should be played against a background of other elements, humor, mood, suspense - so that when the action occurs, it is important.

They used to have this Axiom painted on the wall at Image Comics, I'm told.

So, do you really read (or "look at" I should say) those 10 page shaolin showdowns that keep cropping up in your comics? I know I don't; I just keep skipping to the first part where the butt-whooping is over and actual plot advancement happens...

13 comments:

>>A comic lead story which depends on melodrama can be no stronger than its most melodramatic figure - therefore the importance of strong super-villains.<<

Boy howdy! In my book, the acid test for true-blue, real-deal, flat-out comic book supervillainy is the ability to use the term "accursed interloper" in a sentence, with a straight face. Mustache-twirling is optional.

And in all fairness, back in the day, that was what drew me to Marvel comics, and away from DC. Marvel villains didn't just rant a wicked monologue, they were actually up to stuff, bad stuff, sometimes even scary-bad stuff (by 60s standards). They weren't heisting the jewelery exposition with umbrella-motif nonlethal weapons or riding on giant robot chickens wielding oversized butterfly nets for catching Batman. No, indeed. These guys were standing on the battlements of their ancient castles, waving their arms and raving like loons, with giant thunderstorms raging in the background, as they unveiled their latest doo-hoo-hoomsday devices(!). You could just about hear the organ music swelling up!

The heroes, and sometimes even the writers, seemed to take these villains seriously; they were not just background noise for secret-identity pranks or sitcom misunderstandings. It actually seemed to matter that the Mandarin or the Red Skull get defeated.

Yeah, yeah yeah, that was a long, long time ago, of course, and many things have changed since then, but back in the day, there used to be only one place to go for serious villains.

Great article, Scip.

Thanks for drawing my attention to Sundell's words and work.

"See these? These are the supporting cast for all our principal heroes and they will remain so for the next fifteen years," you'd be surprised how much that would allow those characters, and the heroes they support, to grow in popularity. "Creator freedom" is overrated; I think writers become more creative when the editors give them clearer lines within which they may color (and I think the last several years at DC are evidence of this).

When I read this, I kept thinking that they may have actually done this with Batman's cast.

Editor: "Yes, you can write Batman but you can't kill off anyone."

Next writer: "Okay, fine, but Barbara's going to be in a wheelchair for the rest of her life."

Next writer after that: "Yeah? Fine. But that ain't slowing her down."

And so on. The end result is a strong, layered character with tons of fans and an important role in the DCU.

Axiom 6 is why I suspect that Gail Simone, who understands it, is secretly the illegitimate child of Mr. Sundell. It's also the basis for a story I desperately want to read: "Killer Moth and Cavalier Go Shopping At Wal-Mart".

I thought about this the last time you spoke about it. I'm convinced DC needs an entirely separate title to present "throw-away" stories in, maybe two or three an issue. "Killer Moth and Cavalier Go Shopping at Wal-Mart" would be great for that. And heck, they could bring Killer Moth's daughter from the Teen Titans cartoon shopping too. They could call it "Kitten has Two Daddies".

Of course, I wouldn't settle on anyone except Gail Simone to write.

Excellent post, by the way.

The Absorbascon reminds me of that one class you take in college that's not related to your degree. You take it because you love the subject matter, and you know the instructor loves it too. You go in week after week, never missing a class, eager to learn and dissect and discuss.

Thanks, teach.

Sundellian Axiom 4

...The denouement is the breathing spell...It does not need to be more than three or four panels, a page at most.

On the whole, most writers get this and do this, I think

Yes, except nowadays those "three or four panels" have been decompressed into whole books or perhaps even a mini series.

Good point, Nimbus!

Paul Dini does it the efficiently, old-style way. I think Johns does ... or at least can, when he wants to.

So, do you really read (or "look at" I should say) those 10 page shaolin showdowns that keep cropping up in your comics? I know I don't; I just keep skipping to the first part where the butt-whooping is over and actual plot advancement happens...

Comics may be a "visual medium" but too many writers & artists take that too literally. Bruce Lee movies were all about the kick-ass fight sequence, but translate those into comics and it loses its impact.

I sometimes scoff at characters who deliver an entire monologue during one punch of a fight sequence, but I need some development of the story to make the fight worthwhile.

With the exception of #1 these Axioms should be handed out to any writer taking a job in the comic industry.

Um, could you e-mail this list to Mark Millar, JMS and the rest of the Marvel brain-trust?

It's amazing how many of these axions have been broken by recent writers of Spider-Man, and how much the character has suffered for it. Especially in terms of the supporting cast.

Reading Axiom #4 and your response, I was immediately reminded of Neal Adam's Skateman, which provides an excellent example of ending on a climax.

The review this image comes from notes how jarring the effect is.

Eh. Didn't work. Well, just look for the Skateman review at the old Gone & Forgotten site.

Y'know, if you're so inclined...

Very cool piece, Scipio. I don't think I'd ever head of Sundell before.

That first axiom is a whopper, and I'd actually call it even more relevant in these "post-universal" days. Who wants to read a Batman who isn't still the total of heroic qualities, even out of his own strip? So it should be the jumping-off point of craft for modern longjohn writers to make sure that he is.

It's like Toth for writers! Very interesting.

I posted a long comment yesterday, which apparently got eaten.

But #4 (about the need for a "denouement" of some sort) seems to address a problem that was fairly common in his era for some reason.

You also see it in a lot of movies - for instance, a bunch of the Universal monster movies just end as soon as the monsters are killed or whatever. It seems really abrupt to modern eyes, which expect at least a brief shot of, e.g., the boring human hero and the girl embracing, or something of that sort. The later Hammer movies do this a lot as well.

Scipio's post also provides a fine eleventh axiom to add to this list: "The Composite Superman is pure coolness, and should be used at every opportunity." I agree with both Abner and Mr. Garling.

Post a Comment