As I recall, a new issue of the Flash comes out today. This is my attempt to convince you to buy it.

I know I’ve already discussed how pleased I am with Flash recently, but I feel the need to unpack that a bit. It’s not just that the writing is good and that the art is good (although they certainly are). Those are wonderful things! But they are fleeting. They adhere in each particular story, but by themselves they do not necessarily improve the character in ways that help future creators.

In short, great art and great writing make for a great story, but they don’t necessarily make the character greater. But choices about what to do with a character and their central elements can make them great—even in the absence of great writing and great art.

For example, I know some of you do not think Geoff Johns is a great writer. I like his work, but I will still concede that he tends to use gratuitous graphic violence, his good guys seem to win mostly because they’ve reached the point in the story where he needs them to, and he has trouble ending a story. But whether you think his writing is great, there is little question that his authorial decisions succeed in making the characters greater, as the long list of characters (many considered irredeemably toxic) he has revitalized makes evident.

Certainly, as we saw last week during “Wolf Week” here at the Absorbascon, great art does not make a character greater. Neal Adams’ overwhelming genius depicted in gorgeous, unforgettable detail just how stupid the Stupid Bronze Age Batman was.

But, even in the absence of great writing and great art, an author can still be remember for doing great things with (or for) a characters. James Robinson’s Starman series comes to mind. The art was always blocky, crude, murky, or just plain off. Robinson had a lot of trouble plotting the series consistently and often seemed to lose his way amid the details of the Starman legacy and the fictionopolis of Opal City. But, oh, what glorious details they were! And that is why his work on Starman is remembered so fondly, not because the prose, or the plotting, or the pictures were so stellar, but because Robinson’s character choices and world-building were so powerful and unforgettable. Heck, I never did figure out what was up with that dwarf; it was all very Twin Peaks there for quite some time.

When I complained in 2006 about how tedious and misguided the Flash series had become because its concepts were so far off-base: a commenter replied, “I think the concept is the least of the current Flash comic's problems. The writing and art are just plain bad.” I respectfully (still) disagree: if there is a problem with the concept of a character it is NEVER the least of the character’s problem. If the writing and art are bad, the fix is not complicated: get a better artist and a writer. I am NOT saying that it is easy to get good writers and artists; but the solution is not a complicated one. Melpomene knows, some of our most enduring characters in modern literature were launched in horrible books with awkward plotting, turgid pacing, and painful prose.

One year, as a horror movie fan, raised by a horror movie fans, it hit me: I had never read the original version of most of horror’s classic monsters. So I sat down and read Frankenstein, Dracula, the Invisible Man, Dr Jekyll & Mr Hide, the Phantom of the Opera. And you know what? They were, on the whole… bad. Tedious. Painful, even. These classic monsters survived, thrived, and grew in fame was not because they were written particularly well, but because the underlying concepts were so incredibly powerful.

Fixing the underlying concepts of a character is therefore more important to the character’s longevity. You know how many Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman stories are either badly written or badly drawn? MOST OF THEM. But their underlying concepts are strong enough to withstand poor handling by creators.

And what Francis Manapul is doing is not just bringing great writing and brilliant artistic vision to his depiction of the Flash; he’s fixing the Flash’s underlying concepts and in two very specific ways.

One: he’s created a “mental power” for the Flash in the form of his “augmented cognition”. Having a mental power of some type is almost essential to having a well-rounded iconic heroic. Superman is super-smart, Aquaman has his telepathy, Green Lantern has his willpower and imagination, Shazam has his wisdom, Wonder Woman has her lasso of truth (essentially a mental power rather than a physical one), Batman is the World’s Greatest Detective, even Spider-Man has his spider-sense. And now Flash has his augmented cognition which allows him to use his mental super-speed to see all possible outcomes of a situation.

Two: Manapul has been very cleverly limiting the Flash’s power… without limiting the Flash’s power. Face it, one of the issues in writing the Flash has always been that his power is so great that it can make him seem unbeatable. Flash’s augmented cognition comes with a downside: option paralysis and loss of perception of the “Now”. As for Barry’s ridiculous physical speed… he still has it, but it now comes with a downside: the rifts in space-time he creates if he generates too much “Speed Force”. And these are just the intrinsic limits to his power. He’s also crafting new villains “immune” to Flash’s speed (Mob Rule’s ability to be in many more than one place at a time) and giving old villains the ability to nerf Barry’s powers (such as Captain Cold’s new dampening of kinetic energy in his surrounding area).

Manapul’s writing is great. His art is fantastic. And what he’s doing with the Flash is even better.

Who thinks to karate chop a werewolf?! I have seen a lot of werewolf movies; in none of them does the logical solution ever seem to be "I will karate chop the werewolf". Stupid Bronze Age Batman.

Who thinks to karate chop a werewolf?! I have seen a lot of werewolf movies; in none of them does the logical solution ever seem to be "I will karate chop the werewolf". Stupid Bronze Age Batman.

Yeah, you heard me: Starman.

Yeah, you heard me: Starman.

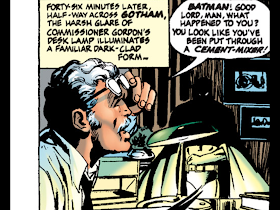

MEMORY: In the Bronze Age, narration boxes often began with inelegant capstone words that made you think that the author pictured himself to be a screenwriter, or maybe a robot.

MEMORY: In the Bronze Age, narration boxes often began with inelegant capstone words that made you think that the author pictured himself to be a screenwriter, or maybe a robot.

"Crud"? "CRUD"!? "Crud" is not a Batman word. Batman does not talk like a tough but virtuous trucker coming to the aid of a sexually harassed diner waitress in a low-budget action movie. Stupid Bronze Age Batman.

"Crud"? "CRUD"!? "Crud" is not a Batman word. Batman does not talk like a tough but virtuous trucker coming to the aid of a sexually harassed diner waitress in a low-budget action movie. Stupid Bronze Age Batman.  "Um, hey, readers, here's your villain and that's why he doing bad things. Like climbing up the side of a residential skyscraper for no particular reason to break into a random apartment with no motivation or goal. Hey, is it Happy Hour yet?"

"Um, hey, readers, here's your villain and that's why he doing bad things. Like climbing up the side of a residential skyscraper for no particular reason to break into a random apartment with no motivation or goal. Hey, is it Happy Hour yet?"  " 'Tis said it takes a special lack of talent to survive in Bronze Age comic book writing... a mixture of sheer nerve, amateur pretentiousness, and a casual acceptance of otherwise unbelievable prose and plot."

" 'Tis said it takes a special lack of talent to survive in Bronze Age comic book writing... a mixture of sheer nerve, amateur pretentiousness, and a casual acceptance of otherwise unbelievable prose and plot."  "Yer a funny guy, Jim; wanna find out just what the inside of cement-mixer is like some time? Keep it up."

"Yer a funny guy, Jim; wanna find out just what the inside of cement-mixer is like some time? Keep it up."  The dirt-streaked window of a dimly-lit pharmacy?

The dirt-streaked window of a dimly-lit pharmacy?